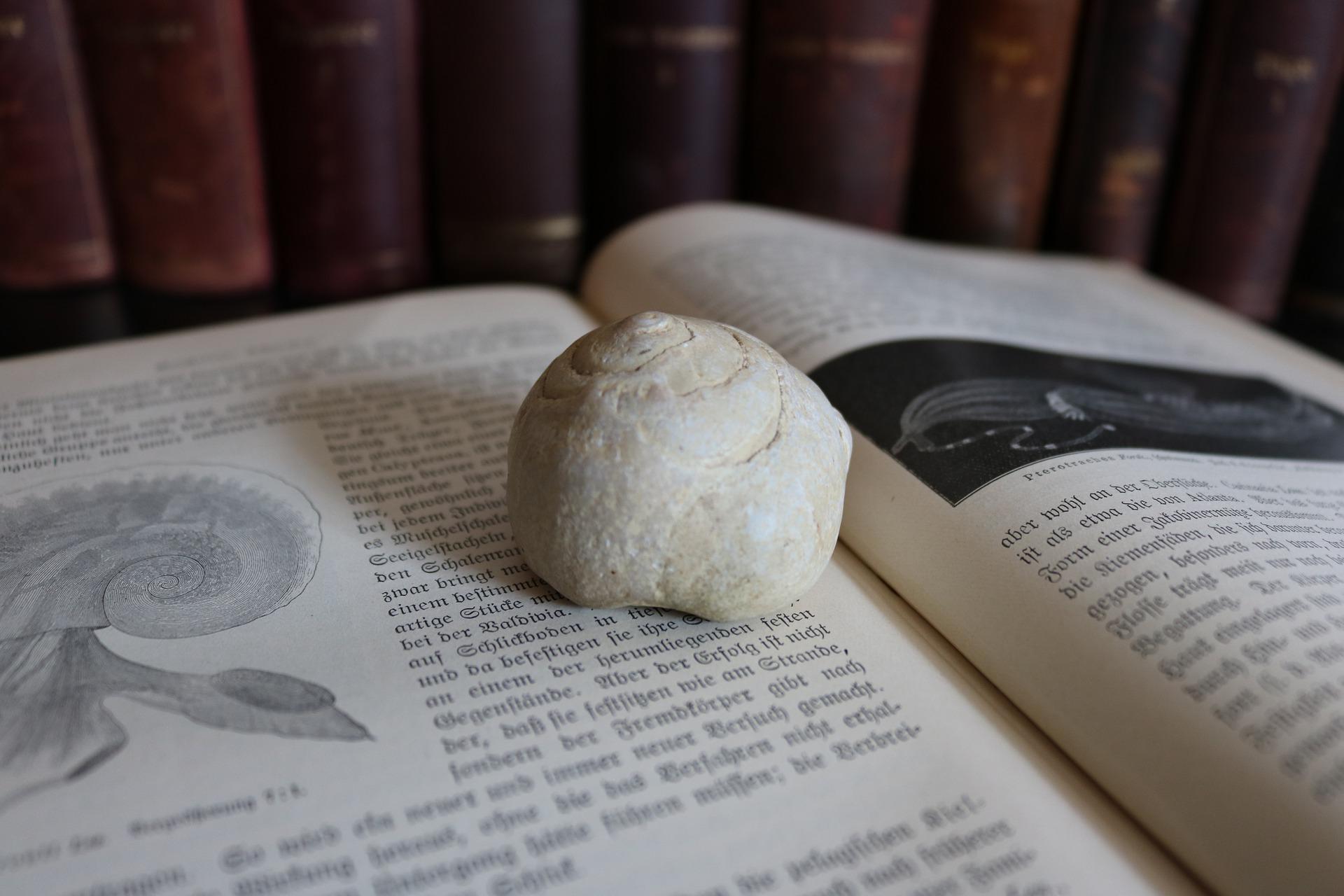

Image by Christian Storb from Pixabay

I can’t shake money from my mind. It features prominently in this age of pervasive central banking, Wall Street bailouts, investment market obsessions, and cryptocurrency culture wars. Many seem to have prospered by betting big on money-related investment themes from speculating on Bitcoin, to buying profitless technology stocks, or shorting volatility. Yet, for all its use, money remains a confused topic. It lacks a uniform definition. Worse, money has many and conflicting ones rendering the concept almost meaningless. Money seems to be whatever one wants: gold, fiat currency, cryptocurrency, bonds, derivatives, etc.

Yet, there’s hope for resuscitating money from its unusable state. After all, it wasn’t always confusing. Even the earliest humans used money. Looking back through history, I found ample support for money’s proper conceptual use. In fact, today’s many definitions still retain its remnants. All (implicitly) acknowledge that money facilitates exchange. It is, and always has been, a common unit of measurement for economic value (only).

Harmony within the conflict

Money’s most popular definition belongs to William Stanley Jevons. He famously attributed four functions to money as a: 1) medium of exchange; 2) common measure of value; 3) standard of value, and; 4) store of value. Scores of economists have since (and prior) defined money as some combination of these four functions. From them sprung numerous economic theories.

Yet, money definitions conflict in many ways. Is money a commodity or debt? Do governments create it or is money endemic to private trade? Is gold money or a shiny rock? Can banks conjure it from thin air? Each of Jevon’s money functions yields a different answer. Thus, it’s no surprise that we have such varying economic opinions.

However, there are two aspects of Jevon’s four money functions common to all. First, money relates to exchange. No transactions, no need for money. A man alone on a deserted island has no need for money. Only when joined by a companion does money enter the scene. Money is a tool for trade. It allows people to swap various goods and services by expressing them in common terms. As Aristotle noted:

Money, then, acting as a measure, makes goods commensurate and equates them; for neither would there have been association if there were not exchange, nor exchange if there were no equality, nor equality if there were no commensurability. … There must, then, be a unit, and that fixed by agreement (for which reason it is called money); for it is this that makes all things commensurate, since all things are measured by money.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics (4th century B.C.)

This leads to the second common aspect implied in all of Jevon’s money functions (and stated by Aristotle): Money is a measurement concept. It expresses economic value in common terms. Whether buying and selling goods and services or saving for the future, money’s used the same. It quantifies value in a shared language. One question subsumes its every use: How much? How much does the widget cost? How much have I saved in my investment portfolio? The answers are quantities of money—a common measure of value.

Money’s historical use

Yet, a proper definition must be more than linguistically consistent. Making sense is not enough. Definitions distinguish concepts from each other. Thus, they must correspond to reality to be useful. Otherwise, they will lead us astray. Money’s consistently been used as a common measure of value throughout the eons, bolstering its position as such. It is money’s essential characteristic.

Truth is the product of the recognition (i.e., identification) of the facts of reality. Man identifies and integrates the facts of reality by means of concepts. He retains concepts in his mind by means of definitions. He organizes concepts into propositions—and the truth or falsehood of his propositions rests, not only on their relation to the facts he asserts, but also on the truth or falsehood of the definitions of the concepts he uses to assert them, which rests on the truth or falsehood of his designations of essential characteristics.

Ayn Rand, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology

Money’s various manifestations have been well documented. Professor David Graeber surveys many—spanning cultures, geographies, and time periods—in his book Debt: The First 5,000 Years . While not his objective, Professor Graeber provides ample support for defining money as (only) a common measure of value.

This was most evident in primitive societies such as the Tiv of Central Nigeria and in Medieval Ireland. Both measured value in terms of human beings, though they didn’t necessarily transact in them.

The Tiv viewed marriage as an exchange of women by men (moral judgement aside). Thus, only another marriage-age woman could rightfully compensate a family for marrying off one of its own to another man. This, of course, created a coincidence of wants dilemma common to barter. “Fair” trades—i.e. woman for woman—were difficult to find. The Tiv, however, constructed a workaround. They came to accept payments of special brass rods in exchange for wives. However, no amount of rods could fairly amount to a human life. Thus, payments continued for years beyond weddings. For the Tiv, women were the common measure of value in these transactions. Individual, marriage-age women and, more commonly, brass rods mediated exchange.

A similar phenomenon occurred in Medieval Ireland around 600 A.D. People used the cumal as money. The cumal, though, was strangely defined. It equaled one slave girl (again, moral judgement aside). While various debts, such as legal fines, were calculated in terms of cumals, slave girls were (thankfully) not used to transact. Rather, elaborate penal codes converted cumals into other items with which people would, such as cows, pigs, or various foodstuff. Like the Tiv, the unit of account and medium of exchange were separate.

Credit also routinely mediated trade. Accounting systems arose to track credits and debts among people without exchange mediums, like coins. The Sumerians in Mesopotamia, for instance, created one of the earliest known systems with clay tablets and cuneiform writings. Tablets tracked credits and debts in terms of standard weights of silver called shekels. However, payments rarely occurred in silver, as Professor Graeber notes. Debts were typically settled in “more or less anything.” Barley was most commonly used, as were items like goats and furniture.

There are many more examples. Wooden tally sticks recorded debts in medieval England. Knotted strings and notched strips of bamboo and wood were used in China, similar to the Incan khipu method. Luigi Einaudi documented how French kings in the time of Charlemagne kept accounts in Roman money even though none circulated. People traded with locally minted currency. Alfred Mitchell Innes noted how early, colonial Newfoundland fishermen swapped dried fish for supplies even though values were calculated in pounds, shillings and pence. Cod and staples traded hands, not official currency.

Even metallic content in coins, it seems, did not serve as monetary standards. In his 1913 essay, What is Money, Mitchell Innes illustrated the large degree to which similar coins varied in their metal content and purity. For example, ancient Greek coins greatly varied in metallic composition. Some were mostly gold, others were mostly silver, and some were bronze. Yet, they represented the same value. This also occurred in France between 457 and 751 A.D. where the Sol (or Sou) was the monetary unit. Some were pure silver, others were pure gold, and some were alloys. Thus, Mitchell Innes concluded that circulating coins were tokens. They were currencies; “the monetary standard was a thing entirely apart from the weight of the coins or the material of which they were composed.”

Separate and not equal

Historically speaking, mediums of exchange and the common measure of value have always been separate concepts. Money, it seems, never played both roles. Whether transacting in gold coins, copper ingots, shells, beads, livestock, brass rods, feathers, or salt, none served as a common measure of value. Rather, they mediated exchange as currencies to settle transactions measured in money. These token currencies only represented economic value and served as proof to those who possessed them. Currencies and money are different concepts.

The store of value function suffers a similar defect. People preserved wealth in numerous items throughout history from crops, to diamonds, to publicly traded equities. None, however, served as a lasting common measure of value. This function, too, is separate from money. It’s savings. Like currency, savings can be quantified in money terms for planning purposes. Savings fund such delayed consumption as home purchases, college tuition payments, retirement living expenses, gifting, and insurance for unforeseen needs.

Aristotle nailed it again

Money is a confusing topic today. It’s widely accepted to perform four main functions as a medium of exchange, common measure of value, standard of value, and store of value. However, few agree on which four apply. Thus, money suffers from having many and conflicting definitions which leads to vastly different economic conclusions.

Yet, money is an ancient concept. The earliest humans used it for two purposes. First, money facilitated exchange between people. An isolated human has no need for money. Money specifically did this by, secondly, quantifying the value of goods and services into a mutually understood language. In other words, money was a common measure of value. This use is evident in all cases, from primitive to modern.

Thus, money is a distinct concept from mediating exchange or storing value. I call the former currency and the latter savings. Much of our economic confusion stems from conflating these three distinct concepts. Money has just one function.

Definitions play a critical role in human cognition. They form the bedrock of knowledge. To no surprise, rediscovering money and logically (re)defining it has significantly furthered my own grasp of economics and investing. Aristotle nailed it again.

If you enjoyed this article please consider sharing it with others.

You actually made a very interesting point about the separability of the three elements of the typical textbook definition of money, namely “unit of account,” “medium of exchange” and “store of value.” Now I will post a few attempted examples of real things that have only one of these functions, and we can see how “money-like” or otherwise they seem.

Pure store of value: physical assets such as works of fine art.

Pure medium of exchange: game and ride tokens at an amusement park.

Pure unit of account: the Special Drawing Rights used by the IMF to keep track of foreign currency holdings of its members.

Poker chips are an interesting case. During a game, they act as a unit of account, providing a measurement of who’s winning by how much. Outside a game, they act as a medium of exchange, as many casinos will accept the chips as payment for goods and services.

So yes, you’re right these functions can exist separately. I’m much less convinced of the usefulness of redefining the term. What new insight does one gain by calling Special Drawing Rights “money”? Still, if you are going to add more details in future posts or in your upcoming book, I’ll be pretty interested to see your explanations.

I appreciate all your comments. I’ve been “chewing” on this idea for a few years now, and admittedly, am still working through it. The blog is filled with iterations in articles and podcasts (a bunch are referenced at the end of this article, in the report linked here, in interviews, etc.). This perspective greatly impacted my approach to economics, finance, and investing for the better.

I haven’t seen anything new here recently, so I’ll wrap up. I previously posted claiming that value isn’t something that can be objectively measured. The reply was along the lines “yes but the prices are open and universal.” In that case, it seems to me the definition “money is the unit of measurement for value” boils down to “money is the unit in which prices are quoted,” and the definition of a price is “the quantification used for regulating the exchange of goods in the market.” The “unit” part of this definition corresponds to the “unit of account” role of money in conventional definitions found in standard economics texts, and the “exchange of goods” part of this definition corresponds to the “medium of exchange” role in such definitions. Am I wrong? If so, how and why?

Value can be objectively measured, just like an inch can. Pick an objective standard (ie something independently observable, which is what objective means) and then see what price the market ascribes to it in terms of that standard. With length, for example, we use inches. 2 people will equally measure the same distance in terms of inches. The same goes for transactions; they are observable to all. Apples cost $x at retailer XYZ today. That is not disputable. We all see the price. This does not mean that you agree with the value proposition for the item at the stated price. That is separate (and will factor into whether you buy the apples or not). Yes money and “money of account” as Keynes used (I believe) are one in the same. Money is the quantification concept. The monetary standard is the specific language used to express the quantification, like the metric system is one for distance. Price is just the measurement, like 3 cm.

I think you are using “price” interchangeably with “objective value” here, which seems to me to be mere playing with words, but I’ll leave it. On the main point, we seem to agree that “money is a unit of account.” But what do you think of the other point, “medium of exchange”? To my mind, a unit of account makes sense only when meaningful transactions are taking place, i.e. exchanges of products and services.

The third major role we usually see in a textbook definition of money is often called “store of value,” meaning that it should be a relatively stable asset class. In my opinion, while it’s a desirable property for a currency, it’s not essential. A currency that experiences volatility is still a currency. Do you agree with that?

I define money as just a unit of account. I separate medium of exchange and store of value as distinct concepts. I call the former currency and the latter savings. They are applications of money – i.e. they use money. Currency and savings are denominated in money units. Both presuppose the question of how much. How much does the widget cost? How much have I saved for retirement? These concepts require the existence of money first in order to function. The widget costs $5, here’s currency to purchase it. I have $1 million saved for retirement and am in good financial shape. Separating currency and savings clears up lots of monetary confusion and has helped my investing. For example, is gold money? Is gold an inflation hedge? Is crypto money? Does the Fed create money? Do banks make money from thin air? All of these complicated issues melted away once I defined money as just a unit of account.

But then it is a unit of account of what? It seems we’d still have to argue whether a price is a measurement of something underlying. If you buy an apple at retailer XYZ, it costs $x, but if you buy a thousand apples, you can probably negotiate a volume discount and it will cost less than 1000 * $x, unlike the case where the length of a thousand one-inch items is 1000*inch. I say that the price is the result of decisions that buyers and sellers make during transactions, in other words exchange is an essential part of it. “Is gold money?” Under your definition, that is equivalent to “is gold the unit in which prices are quoted” and the answer would be yes, in economies that are on the gold standard. So yes, in the US of a century ago and no, in the US of today. “Is gold an inflation hedge?” I don’t see how your definition makes this problem melt away. “Is crypto money?” A lot of businesses accept payment in bitcoin, but they generally quote their prices in dollars and convert at the current price of bitcoin, so your definition would say no. Does the Fed create money? They issue banknotes in dollars, which are widely used for quotes of prices, so your definition would say yes. But can you explain how these answers would help with investing? For any given form of money, you still have to look at its underlying soundness, do you not?

You’ll have to wait for the book to get more. This topic is too big for comment chats. But I’m sure I’ll leak out more as blog posts over the coming year(s).

And how is money created? “Through the act of a puchase.” — E.C.Riegel

Alfred Mitchell Innes further stated: “…credit, and credit alone is money.”

If there is ever to be individual liberty, there must be separation between Money and State.

Private exchange requires private money.

Honest exchange requires honest money (value for value)

Thank you for your calm, rational explanation of the money concept. A 5,000 year old conceptual tool that is presently a politicized government monopoly which distorts all contracts; past present and future.

Maybe someday…

Hello Richard. I’m with you on the separation of money and State! My position is that money needs to be objective (i.e. available for all to observe). Just like we all know how much distance an inch spans (approximately), we should all approximately know how much effort/thought/capital it takes to produce a $1 of value (not possible with fiat currency since there is no standard by definition). Governments should be out of the currency business (which leads to debasement). The market will best decide monetary standards.

We used to have private money in this country. Banks issued notes theoretically redeemable in gold. It didn’t work out all that well.

Thanks for you comment. I had thought the same until I really researched the topic. It turns out that lots of the banking issues related to regulations restricting banks’ abilities to branch and forcing them to back note issuance with government bonds (the supply of which constricted when the US gov’t repaid its debt). Private note issuance worked remarkably well where and when tried throughout history. Here’s one recent article that discusses this topic more: https://www.alt-m.org/2021/07/06/the-fable-of-the-cats/

“Factual definition” was a very unfortunate choice of words here, but I’ll let that pass.

What’s unsatisfying about this definition (“money is a unit for measuring value”) is that we then need a definition of “value,” and that comes up against many problems.

Consider an auction. A room full of people in the same place, at the same time, bidding to purchase the same item, and yet different people are willing to pay different amounts of money.

Consider the stock market. The price of a share of any given stock goes up or down every second. Sometimes by a lot.

Investors whose goal is value preservation typically won’t keep their assets in the form of money alone. That’s because although money may represent value at one instant in time, it’s not guaranteed to keep the same value across different periods of time.

So I don’t think “money is value and that’s all it is” is enough to capture a complete picture of the way people use money. We’re back to the drawing board of all those other more complex definitions you mentioned.

Hello Joe, thanks for you comment. I agree, a monetary unit should, could, and once was defined; but is no longer under a fiat system (by definition and design). For example, weights of gold were used in the past. This defines value in terms of human action (since gold must be produced). Money is an abstract concept. It’s how we quantify value; the standard for which value is objectively measured. Just like length is the measurement concept for quantifying spatial distance. I concretize this abstract meaning in analogy form: Money is to length as dollar is to inch.

I don’t see how a single commodity can provide an objective definition for value. Yes, gold must be produced, but so must every other good and service, and their prices in gold terms also change from moment to moment, from person to person, and from place to place. For example, the ratio of the price of silver to the price of gold is not a constant, as it should be if “precious metal = value.” Techniques of gold production change over time. Geographic distribution of gold reserves change over time. Demand for gold changes over time. So I see no basis to claim that gold captures an objective and repeatably measurable thing called value.

By objective, I mean observable to all. We can all, for example, observe the same price of gold (if we’re looking at the same market quote). Just like we can all observe the same distance that constitutes an inch (so long as we’re all on Earth). Objective standards allow us to quantify reality to each other so that we can use the information for other purposes, that’s about it. I’m not married to gold for such a standard. I think the market would innovate over time to a new standard. But gold was both a market-derived innovation and effective.

If the only requirement is transparency, that applies to many things traded on global markets. The prices of gold, silver, other commodities, shares of stock, exchange rates between currencies, etc. are observable to all. But does that mean these are all standards of measurement of an underlying value? They aren’t consistent with each other over time. Repeatability is what establishes the precision of a measurement, and it is lacking.

Maybe my argument was not clear enough, so now I’m replying to my own post. The fact that the gold-silver ratio is not stable shows that “value as measured by gold” is not the same concept as “value as measured by silver.” The same product or service can see its price in silver go down at the same time as its price in gold goes up. The same is true for all other forms of money in use. If “money is the measurement of value,” it follows we must have different kinds of value for each form of money: “value in gold,” “value in silver,” “value in dollars,” “value in euros” etc., and those will not generally track with each other. Under that definition, I’m not seeing “value” as a truly measurable thing independent of the form of money that is supposedly measuring it.

OK so I was a little flip about private banking, but I do wonder what people expect when they invoke private money or private banking. Mr. Selgin references a Scottish model, which as far as I can tell resembles banking in New York at around 1900. There was a group of private banks with their own private clearinghouse, the banks having at least some kind of relationship with each other, and presumably able to help each other out in periods of stress. I don’t know all the specifics of their backing (government bonds, whatever) but the fact is that any bank’s liabilities are backed by its assets which in every case mostly consist of future payments on mortgages and other loans they have made. If I remember correctly, in 1907 one of the New York banks owned by a Montana copper king made large loans to its owner. Rumor started that the copper king might default, and this started a run on his bank, and other banks were reluctant to step in because they were beginning to get runs of their own. At any rate, things snowballed until an outside agent — lender of last resort, in other words — stepped in (J. P. Morgan, in this case).

I really don’t see much difference between that and today’s banking system, in which money in the form of deposits is created out of thin air by private banks, backed partly by reserves and capital but mostly by future payment streams from mortgages, loans, etc. The difference is that the Fed is now the lender of last resort and an agency of the Federal Government insures deposits.

This whole issue brings to mind people saying “we don’t want the government involved; we’ll just get together and do it ourselves.” But what is government if not We the People getting together and doing things?

All of that is off topic from your original essay, for which I apologize. On that topic, I’ve always found the functional definition of money (medium of exchange, unit of account, store of value) to be unsatisfactory. A list of functions is not a definition. Telling me what money does is not the same as telling me what it is.

There’s a lot here, so I’ll just provide some brief comments and hopefully some helpful references. 1) on “free banking” I highly recommend the works of George Selgin and Larry White (free banking history only). Discovering their works is what led me to blogging and started me down my current path of thinking. There are important differences related to moral hazard, justice, access, cronyism, system fragility, and more that central banks create. Alt-m.org and some links on my What I’ve Read page; 2) Government is a big topic, and one’s view of it leads to one’s economic opinions (including money and central banks). I’m with Ayn Rand that government is outsourced force that we voluntarily empower it with for the purpose of protecting individual rights (only): http://aynrandlexicon.com/lexicon/government.html; 3) Yes, money’s function does not define it but follows from “what it is”, which is why I’m spilling so much ink over it. I hope you’re enjoying it.