Image from Pixabay.

Gold is lots of things to lots of people. To some, it’s the ultimate store of value and a source of financial freedom. To others, it’s just a shiny rock with an inflated, emotionally-driven price. Gold’s most popularly used to hedge inflation risk; to preserve purchasing power from thieving bureaucrats and central bankers seeking to fund government expenditures via currency debasement. However, gold is not as effective as many think in this regard. Oddly enough, the change in monetary regime lessened gold’s ability to hedge inflation.

To be sure, I’m sympathetic to the bull case for gold. I own some in my own portfolio as of this writing. However, the data don’t support its efficacity as an inflation hedge as I believed. Gold doesn’t appear to protect against rising consumer prices. Rather, it seems to have other value drivers. This is no surprise, really. Gold’s relationship to money changed. Hence its relationship to inflation changed too.

Gold’s historical protection

There are countless accounts of monetary debasements throughout history. Kings, emperors, and governments of all stripes routinely looked to their currencies as means to fund their expenditures. Rather than raise taxes, sell assets, or plunder foreign lands, governments simply debased their currencies. They stole their desired wealth for wars, palaces, pensions, and bribes from citizens and creditors via inflation.

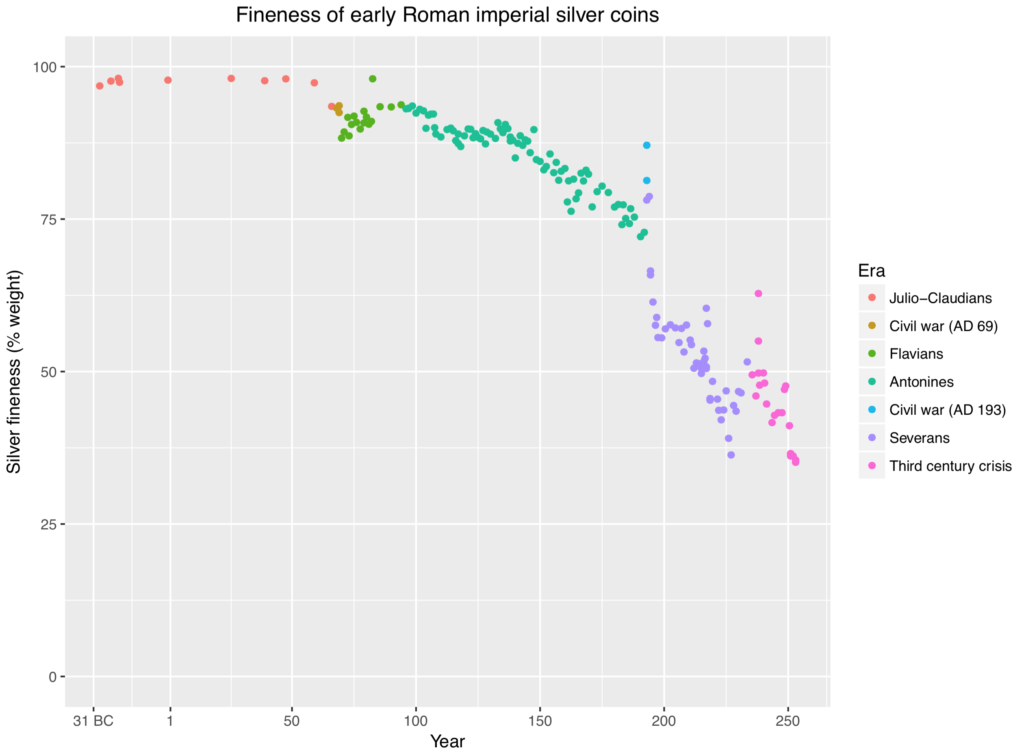

For example, the Roman denarius—the empire’s standard silver coin for nearly 500 years—was continuously debased by emperors. A nearly pure silver coin under Nero in 64 AD contained just 5% by the year 300. More recently, the U.S. inflated the dollar under the gold standard. The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 authorized the near 40% reduction in its value from $20.67 per troy ounce to $35. There are many other examples of governments filling their coffers via inflation too.

“Starting with Nero in AD 64, the Romans continuously debased their silver coins until, by the end of the 3rd century AD, hardly any silver was left.” By Nicolas Perrault III – Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=67224989. Source: Wikipedia

Each monetary inflation was theft. Sovereigns stole precious metals from circulation to use for their own purposes. However, citizens weren’t completely helpless. The fortunate could store wealth in precious metals rather than in currency vulnerable to devaluation. Metals were perfect inflation hedges because they comprised the currencies’ values for which people were actually trading. People weren’t transacting with denarii, for example, but rather the silver content within. Thus, reducing currencies’ metal content (or legal convertibility) lowered the values of currencies, not precious metals.

In other words, the metals, not the currencies were the real monetary standards by which people measured economic value in these examples. This simply isn’t the case today.

Gold no longer protects against inflation

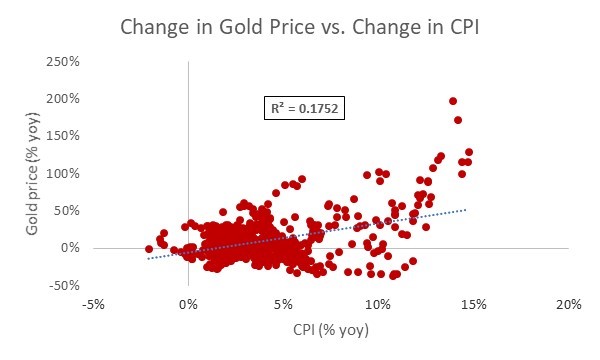

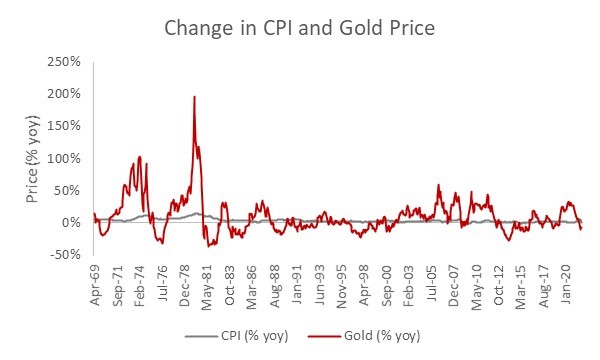

Gold’s primary investment use is to hedge portfolios against inflation risk. However, the data simply don’t support this thesis as sound. Gold’s price weakly correlates with common measures of inflation and is far more volatile these days.

Gold’s price weakly correlates with common measures of inflation and is far more volatile between 4/69 and 10/21. Source: FRED

As the charts above illustrate, gold’s price bears little resemblance to today’s most popular measure of inflation—the consumer price index (CPI). An effective inflation hedge would move in (near) lockstep. It should rise and fall along with inflation. Gold’s price movements, however, don’t. They are more volatile and mostly move independently of inflation, apparently driven by other factors.

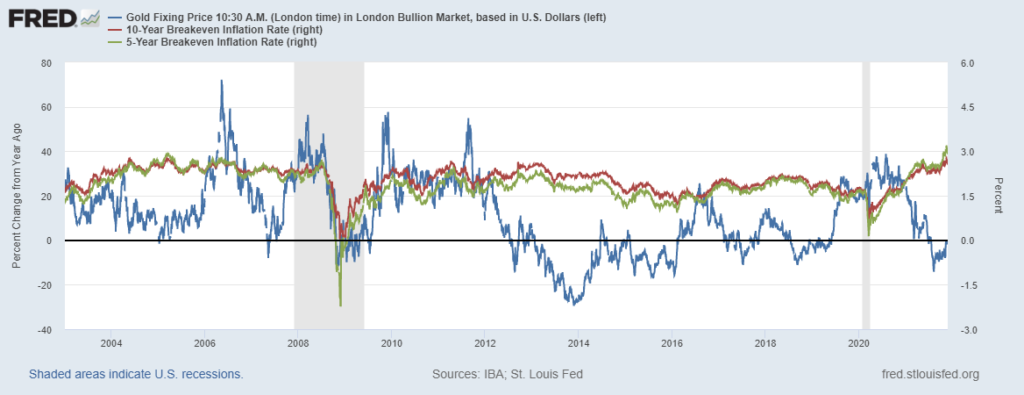

Gold’s price does not correlate with inflation expectations either. Source: FRED

Nor does gold’s price correlate with inflation expectations, as shown above. Here too, gold’s price would rise and fall along with the market’s outlook if it were an effective hedge . However, no relationship exists.

Gold’s relationship to money changed

This is all quite puzzling on the surface. How can gold be disconnected from inflation? Why is our modern experience so different than the historical one? The reason, in my opinion, is definition changes—for both money and inflation.

Throughout most of history, monetary standards were defined. Precious metal regimes are the most famous examples, though there were others. At one time, $20.67 U.S. dollars was defined as an ounce of gold; the Roman denarius was a coin that contained 4.5 grams of silver. While people most commonly used currencies—the medium of exchange—they were actually trading in terms of those precious metals which were the (implicit) standards for measuring value.

Thus, governments debased currencies (and created inflation) by reducing their precious metal content (or convertibility). While monetary standards changed (i.e. the amount of metal content in each currency unit), the metals’ values, of course, did not. Thus, prices increased in currency terms. However, they remained (relatively) constant in precious metal ones. Hence, direct gold ownership protected against inflations.

Today, however, we have fiat money regimes. There are no monetary standards, by definition. A dollar has no codified value. Rather, it’s worth whatever it fetches in trade. Hence, inflation, in the classical sense, is impossible. There simply is no monetary standard to change! Using the change in CPI (or some equivalent method) as an inflation-gauge is a (flawed) workaround.

Trade requires a common language for value just like construction requires one for length. Gold (or rather its weight) played this role historically. Today though, it does not.

Absent its special role, gold’s just another “hard asset”, like real estate, corn, or art. While money printing by sovereigns might increase gold’s market price, there’s no assurance that it must. If the Federal Reserve conjures more dollars, those new dollars (first) impact prices where they are spent (or by those who react to it). Gold’s price may or may not change. This differs from a gold standard where its price must—by definition—change in lockstep!

The first change [in price] occurs at the point where the additional money is introduced into or taken out of the economy and is expressed in an increased or decreased demand for the goods and services desired by the persons directly affected by the change in the quantity of money.

Clark Warburton, ‘The Misplaced Emphasis in Contemporary Business-Fluctuation Theory‘ in American Economic Association Readings in Monetary Theory

An illustrative example

Let’s illustrate this point with a hypothetical example. Say $10 dollars was defined as an ounce of gold (i.e. a gold monetary standard) and you possessed 10,000 ounces. You’d have $100,000 of purchasing power (10,000 ounces x $10). Now, say we debased the monetary standard such that $20 dollars now equaled an ounce of gold. Consumer prices would inflate by a factor of 2 in terms of gold. Those holding currency would lose half their purchasing power. Not you, though. Your 10,000 ounces of gold are now worth $200,000 and is the perfect hedge!

However, things work differently in fiat currency regimes. There is no explicit monetary standard. Thus, in order to devalue the dollar by half (as we did above) we’d need to double the quantity of dollars in circulation, all else equal. According to theory, this increase in the money supply (or rather currency supply, as I see it) should elicit an equal response in consumer prices. They should (theoretically) double; gold’s too.

However, this won’t automatically happen as it did in the gold standard scenario. There, gold must double in dollar terms because of how we defined dollars. In the fiat case, however, gold’s price might increase; but it might not. Nor would it necessarily do so immediately or proportionately to the currency supply increase. It all depends on people’s spending patterns. Gold’s price rises only if and when people bid it up, like all other goods and services. Thus, the hedge is imperfect at best, and potentially nonexistent, as the previously presented data suggests.

If not a hedge, is gold worthless?

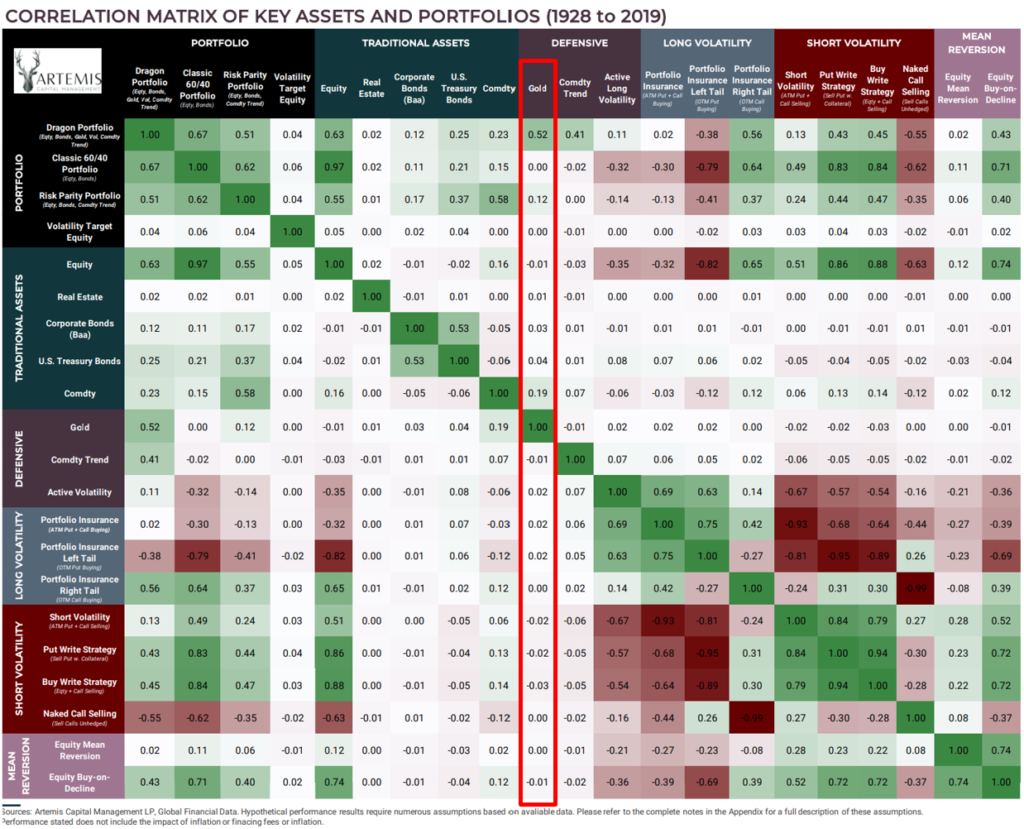

Gold may no longer hedge inflation as effectively as under the gold standard, but it still might have investment merit. For example, one Artemis Capital Management study found that “gold has outperformed the stock market on a price appreciation basis over the past 48 years since Nixon de-linked U.S. dollar-based convertibility on August 5th, 1971.” Their ideal portfolio contains an allocation to the “barbarous metal” due to its large and uncorrelated returns.

Gold’s returns (highlighted in red) are uncorrelated to other popular assets. Source: Artemis Capital Management

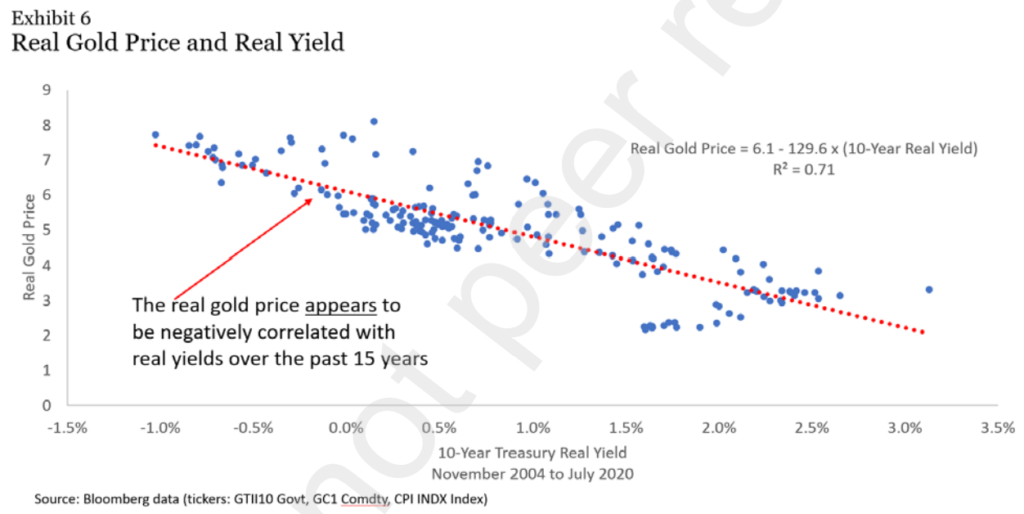

Gold also plays a store of value role in portfolios, performing best when “real yields” are negative and declining. A real yield is an asset’s return excluding the impact of inflation. It’s commonly calculated by subtracting the inflation rate from a notional government bond yield. Since holding gold costs money via storage fees, many prefer to store their wealth in income-earning government bonds. However, a negative real yield implies that this return is illusionary. Inflation is eroding investors’ value. Hence, government bonds lose their cost advantages and market shares to gold in such scenarios.

“The real gold price appears to be negatively correlated with real yields over the past 15 years.” Source: Gold, the Golden Constant, COVID-19, ‘Massive Passives’ and Déjà Vu

To be honest, I’m unsure how much of gold’s value is due to its inflation hedge legacy than to reality. Thus, gold’s future performance could deviate from its past. In my view, utility value is the ultimate inflation hedge. Supply and demand naturally adjust prices even when the money supply inflates. Thus, gold, like any other non-currency-based holding, should offer some protection on these grounds. However, I’m less confident it’s the best or only choice.

More highly polished investment theses

Many people invest in gold for its inflation protection benefits. History is riddled with governments inflating their currencies for personal gains. Gold ownership has been a dependable defense against such thefts.

However, gold’s relationship to money changed. Its weight no longer defines money. Absent this special role, gold is merely another asset. Its price is now subject to the the laws of supply and demand. Thus, gold no longer hedges inflation as perfectly as it once did.

However, gold may still enhance investment portfolios. Its volatile price and uncorrelated returns are attractive features for some. Furthermore, it still protects against inflation by virtue of its utility value in jewelry, industrial applications, and investment lore, in my opinion; just less than it used to.

Identifying how gold lost its inflation-protection luster was helpful for me. Quite frankly, my investment thesis was antiquated. Now, I can better see if and how gold can make my portfolios shine.

Disclosure: I, and accounts that I control, own gold-related assets as of this publishing date.

Other References

If you’re interested in learning more about my views on money and inflation, check out my YouTube show episodes on these subjects below:

Inflation

Is Inflation Still Inflation (6/4/21)

What’s Behind Today’s Inflation? (6/11/21)

Money

- Rethinking the Fed and Money: Part 1 (7/9/21)

- Rethinking the Fed and Money: Part 2 (7/16/21)

- Rethinking the Fed and money: Part 3 (7/30/21)

- Rethinking the Fed and money: Part 4 (8/6/21)

- Rethinking the Fed and money: Part 5 (8/13/21)

- Rethinking the Fed and Money: Part 6 (9/10/21)

- Rethinking the Fed and Money: Part 7 (9/17/21)

If you enjoyed this article please consider sharing it with others.