Image by Kranich17 from Pixabay

Not a day goes by without the need for money. Whether buying a cup of coffee, checking your investment portfolio, or contemplating monetary policy, money is always top of mind. Yet despite daily use, money confounds us. Even experts ascribe mythical qualities to it. For example, many believe that banks create money out of thin air. While seemingly logical at first, such magical thinking falls apart from a real-world perspective.

In my opinion, Professor Richard Werner of Linacre College at the University of Oxford makes the strongest case for banks making money from thin air (the Bank of England makes a similar one, too). He treats banks like modern-day alchemists, using parlor tricks—in this case financial accounting—to bring new money into existence. However, this view, in my opinion, is flawed. It’s too concrete; it too narrowly focuses on banks and fails to appreciate the greater role that money plays in our lives. The “money from thin air” view confuses borrowed money (i.e. leverage) with permanent—i.e. actual—money.

No money, no problem (if you’re a bank, allegedly)

In a 2015 paper, Professor Werner (allegedly) illustrates how banks create money from thin air. He expertly details this process with a 2008 transaction by the Swiss bank Credit Suisse. Soured subprime mortgage transactions left Credit Suisse teetering on the brink of insolvency. The bank needed fresh capital to survive. However, raising it was difficult. Investors don’t readily lend to insolvent banks.

Luckily though, Credit Suisse needed not fret. It was a bank. It could simply conjure some money up. All banks can, according to Professor Werner, and this is precisely what Credit Suisse did. After a few keyboard strokes: Voila! Credit Suisse minted itself £7 billion and was now solvent.

The link between bank credit creation and bank capital was most graphically illustrated by the actions of the Swiss bank Credit Suisse in2008. This incident has produced a case study that demonstrates how banks as money creators can effectively conjure any level of capital, whether directly or indirectly, therefore rendering bank regulation based on capital adequacy irrelevant … [Emphasis is mine.]

Richard A. Werner, A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence

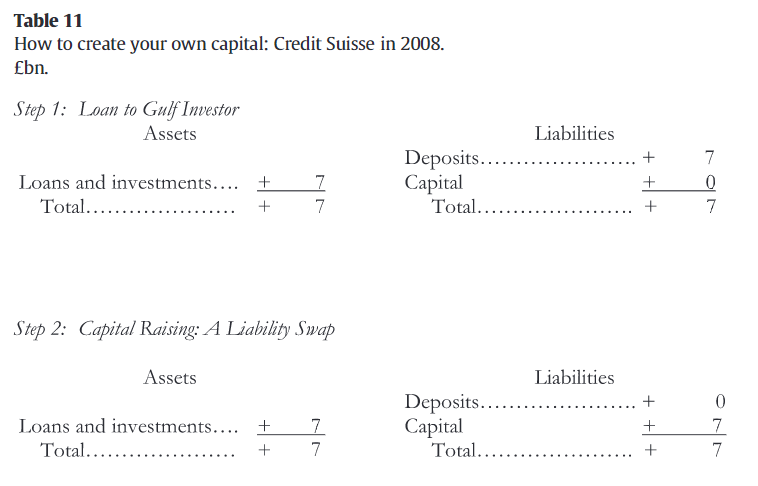

Professor Werner illustrates this process via simplified balance sheet transactions, shown below. First, Credit Suisse makes a £7 billion loan to a new investor (Gulf Investor), which it deposits in a newly opened account. This is shown in Step 1. A credit to Credit Suisse’s “Loans and investments” assets is made to reflect the loan (i.e. an investment). Also, a corresponding “Deposits” liability entry is made to account for the new funds that Gulf Investor can now withdraw at its pleasure. Since Credit Suisse both makes the loan and holds the loan proceeds, no money actually changes hands. Credit Suisse’s bankers don’t move £7 billion from its vault into a new account deposit box for Gulf Investors somewhere. Rather, the bank tracks these contractual fund flows with the appropriate accounting entries. It’s all kosher so far despite Professor Werner’s “fictitious” allegation.

Source: A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence

Next, the real magic happens. Gulf Investor withdraws and invests its £7 billion in newly issued preference shares of Credit Suisse, shown in Step 2 as Capital. Like in Step 1, no money actually changes hands; only the appropriate balance sheet entries are made since the transactions are confined to Credit Suisse. And there you have it! Credit Suisse turned a £7 billion deposit liability into the Capital it desperately needed without actually raising any new money. The bank conjured £7 billion of money out of thin air. It saved itself with a few keystrokes!

Sigh.

Thinking it through in the real world

If this seems magically farfetched, you’re correct. However, it takes an appreciation for corporate finance to see. If you end the analysis where Professor Werner does, then yeah, it seems like Credit Suisse saved itself with made-up money. However, we can’t end the analysis here. We have to examine it more broadly.

Gulf Investor’s £7 billion investment saved Credit Suisse. However, this “trick” worked because the transactions occurred within a closed system. They were self-contained within Credit Suisse. The bank “only” needed to show solvency. It did not have to make an external payment. Thus, no money physically had to change hands, as Professor Werner correctly shows. Had Credit Suisse needed to actually transfer these funds to a third party, it could not. Similarly, Gulf Investor could not withdraw the loan proceeds. In either case, Credit Suisse would have had to come up with the money. The recipient would have demanded some actual means of financial settlement; not “air.”

Even still, the £7 billion lifeline comes from somewhere real. Here, Credit Suisse’s existing shareholders foot the bill via lower future stock prices. Collectively, they will lose (more than) £7 billion’s worth of value in the future. All payments made to Gulf Investor’s preference shares—either dividends and/or repurchases—would have accrued to common shareholders instead. Thus, the stock will be worth (significantly) less than it would have absent the transaction (and had Credit Suisse found another way to remain solvent). In other words, Credit Suisse borrowed the £7 billion from the future.

Let’s say, though, that Gulf Investor’s investment was not sufficient to save Credit Suisse and the bank filed for bankruptcy. The existing shareholders (including Gulf Investor) would get wiped out. However, the story does not end. The bank’s creditors take ownership (bondholders, suppliers, etc.); and Gulf Investor still owes them £7 billion.

Gulf Investor’s preference shares gets wipe out in bankruptcy, however its loan from Credit Suisse does not. It’s still obliged to repay it. Gulf Investor has two options. It can either repay the loan from its other means or it can default. In the former case, Gulf Investor becomes the ultimate source of the bank’s previously conjured money. In the latter case, Credit Suisse’s new owners (the creditors) receive £7 billion less for their claims (i.e. they lose even more money). Either way, someone foots the £7 billion bill that Credit Suisse created. It’s not fictious.

Leverage not magic nor privilege

Professor Werner’s “money from thin air” argument claims that banks’ privileged accounting status gives them this money creation power; specifically, their exclusion from “Client Money Rules.” Client Money Rules require institutions to hold client assets in segregated accounts, off balance sheet. Stockbrokers, for example, keep their customers’ assets separate from the company’s. Banks, however, hold them on balance sheet as deposits, comingled with their own. Absent this subtle difference, Professor Werner claims, banks and non-banks would be the same. Banks could not create new money otherwise.

What distinguishes banks from non-banks is their ability to create credit and money through lending, which is accomplished by booking what actually are accounts payable liabilities as imaginary customer deposits, and this is in turn made possible by a particular regulation that renders banks unique: their exemption from the Client Money Rules. [Emphasis is mine.]

Richard A. Werner, How do banks create money, and why can other firms not do the same? An explanation for the coexistence of lending and deposit-taking

However, there’s nothing unique or nefarious occurring. Rather, Professor Werner fails to appreciate an important difference between banks and non-banks (like stockbrokers). Banks don’t lend their customers’ assets when they make loans. They borrow them! Unlike the investments with your stockbroker, you actually loan your cash to your bank when you make a deposit. This is why your bank pays you for deposits and you pay your stockbroker for holding your assets. While, modern-day “bail-in” regulations have blurred the lines between bank shareholder, creditor, and depositor as Professor Werner points out, they have not fundamentally changed the borrow-to-lend business model.

Thus, the new money made by Credit Suisse in our example is just leverage. Credit Suisse is borrowing it from others and from the future before passing it on to Gulf Investor now. The new money is eventually accounted for in real life, in one way, shape, or form depending on how events play out. Make no mistake, the piper gets paid.

Professor Werner is correct, however, that banks make money; just not from thin air. They do so by facilitating intertemporal exchange. Banks lend borrowed value from the future to those who want it today. Privilege plays no part. As Hyman Minsky observed, “everyone can create money; the problem is to get it accepted.” We accept bank money in return for their vital service of financial intermediation.

… we illustrate that banks are an important component of the money creation process … far from being created out of nothing, bank money is the product of a legal and institutional framework and results from an underlying value-for-value intertemporal exchange transaction that is facilitated by the intermediation of the bank. [Emphasis is mine.]

Robert William Vivian and Nic Spearman, Banks and Money Creation ‘Out of Nothing’

The “money from thin air” argument treats financial accounting as a game. It’s not. All those numbers represent a real-world exchange of value. No one, including banks, can simply make them up. This view wrongly confines money to bank activity. While popular, Minsky is right; anyone can (and does) create money, not just banks. Money is simply a unit of account; hence all economic production is monetary production. Banks produce money by employing productive leverage.

Banks create money from leverage, not thin air

There’s a popular notion that banks create money from thin air. This view permeates academia, markets, and monetary policy discussions. The “money from thin air” argument rests upon a concrete view of money that’s restricted to bank activity and a belief that banks enjoy a privileged accounting status that grants them this power. In my opinion, Professor Werner makes one of the strongest presentations of this view.

However, the “money from thin air” argument is flawed. It too narrowly focuses on banks’ immediate actions and fails to appreciate the broader, corporate finance perspective. Banks borrow money to lend. They intermediate “value-for-value intertemporal exchange.” By employing leverage, banks facilitate value creation. The economic production that follows is the money creation observed by Professor Werner. The “thin air”, however, is leverage, not magic.

Money is much broader than banks. It’s a unit of account for measuring value throughout a society. Similarly, financial accounting is not some game for the privileged to exploit. It’s a tool to track vital, real-world transactions, including money creation. Despite popular opinion: there’s no free lunch and there’s no free money.

If you enjoyed this article please consider sharing it with others.

What you are missing is that when CS made the loan, they actually did create new, usable money. That is, in fact, what banks do: they are the money creators in the economy. After CS makes its loan, the borrower can spend the money anywhere (barring regulatory impediments, which is why this procedure is not often used). You assert that no “real money” changed hands. Really? What do you think is “real money” – paper cash only? Bank deposits are used as real money all over the world. Bank deposits are the form and origin of virtually all our money. You can choose to disbelieve the work of Werner, of the Bank of England, of Charles Goodhart, of Schumpeter, and many other well-informed scholars if you want to, but it will not change the fact that when a bank makes a loan or buys any asset, its balance sheet expands by that amount, and new money is created on the liability side of the balance sheet to pay for the transaction. If this is not an accurate description of how money is created, what is your version of the process? Thanks.

Thanks for you comment Jim. I agree that CS created money here … IF it could repay the funds it borrowed. This intermediation of time – investing capital currently available – is one process of money creation. However, if CS cannot repay borrowed funds, then the money it creates evaporates as the bank fails. This is precisely what just happened. CS tried to create more money then it was capable of, hence it failed and wiped out billions of money previously created.

If this money truly was from thin, without any correspondence to reality, then why do any banks fail? Why not make new money and go about their day?

Yes, (only private) banks make money … or rather, they facilitate the money creation process of production by providing leverage (i.e. resources) to those who use it now to increase economic output which we account for as (new) money.

– I use FRB as an acronym for fractional reserve banking. At first, I thought that banks lend only 0.9 of their capital, but as you mentioned “a bank’s loan portfolio would be 9x larger than its capital/shareholder’s equity”. So I still don’t understand how can you lend more than you have. It is something you would’nt be able to do with commodity money.

– I have read your other article “Invest Easier By Better Defining Money”, and I understand how borrowing money can create extra value that did not exist before, in the micro-level. What baffles me is at the macro-level: the fact that bank lends dollars, but they don’t want you to repay them with wheat, they want their money back (with interset). So the dollars supply will have to grow too, at the macro level.

Simplified, a bank lends out its deposits which it borrows from depositors. This is actual money in the bank’s possession, but it is not the bank’s capital. Deposits are borrowed funds and are owned by/owed to others. The banks has all this money in it’s possession, but its not its own capital/shareholder’s equity to use however it wants. I hope that helps.

Regarding the money supply: you are correct, it should grow in a productive economy as increasing output needs to be accounted for with more money. Ideally, the currency supply (i.e. dollars in circulation and accounts of various bank ledgers) should too, but in lockstep with output. When currency grows more than output, currencies debase. This is what happens when governments “print money.” They are printing currency, not money (i.e. output). As an aside, Bitcoin’s fixed supply is a flaw for its use as money.

Yes it does help, because from reading the Bank of England paper, I understood that a bank can lend as much as it wants (it just changes some bits in the computer), constrained only by market and regulatory mechanisms (and maybe the reserve ratio of x9 relative to their capital). So just to clarify (and I hope I am not circling around the same point too much): when Credit Suisse loaned 7 Billion Euro to Gulf investor, it had to have 7 Billoin Euro in other deposits accounts?

As to your second point, this is an interesting take, and different from what I’ve heard from austrian economists, which claim that a constant supply of money is good, and will lead to falling prices. They will also say (I believe) that since an ounce of gold can buy more under this deflationary system, it will also be able to fund more businesses.

By the way, I know I am asking a lot of questions, so feel free to take a break, and thank you for your thoughtful answers!

wrt to Credit Suisse: it either had to have the EUR7bn up front or be able to produce it in the future. This is a subtle, but important point. If it could not, it would file for bankruptcy and its shareholders, and then creditors, would foot the bill. In all cases, the EUR7bn is accounted for in the real world. It is not just magical accounting with no basis in reality as many peddle.

wrt my the money supply: the longer I write the more I realize how unique my views are. For example, I am a fan of Austrian economics but find myself at odds with some of my favorites in various ways (von Mises’s praxeology, for example). This has been a result of challenging my own thinking. Nearly ever article is the result of a changed view. I hope others enjoy the journey too.

I believe I need to read this again more carefully. But at first, I could’nt ignore the term “borrowing from the future”. Is’nt it a keynesian notion? Doesnt it rest on a premise of “the primacy of consumption”, ie that you can consume something before you have produced it?

Hello and thanks for your comment. All borrowing is a pull-forward of future cash flows: you spend money now that you will payback over time. There is nothing wrong with borrowing as such, and it can be quite productive in the proper context. Borrowing to stimulate, though, is problematic (as I think you imply).

Hey Seth, and thank you for your reply.

What I am trying to grasp is that banks do not operate as FRB (not in the manner I had in mind at least), and they don’t borrow and lend 90% of the existing deposits (on a 10% reserve ratio) but instead borrow and lend 900% of the existing deposits, i.e they borrow and lend something that does’nt exist.

So first, did I understand it correctly? and second, what justify it morally and legally?

Maybe to clarify, I’ll ask: do you think that banks would operate in the same manner under free banking system? What would be the legal conditions for banks in such a society, and how would they actually evolve?

I have in mind another question, which I am not sure is completely related but might clarify my confusion:

At a specific point in time, all the banks in some country are lending X amount of money in the form of green notes. With this money, entrepreneurs are building wealth, which according to your view, is also money. However, the banks are expecting the debt to be paid with X+r (interest) green notes, which doesn’t exist! In order to bring this money into existance, it will have to be created with interset, and it will just go on and on and on. So what is the solution?

There’s a lot here, so I’ll try to address everything concisely:

– What is FRB?

– Banks borrow and lend existing capital; they don’t make anything up (in fact, that is my criticism in this article). Banks lend most of their borrowed capital, but not all capital is borrowed; they are initially capitalized with some equity. Using your 10% example, a bank’s loan portfolio would be 9x larger than its capital/shareholder’s equity (not deposits). This is the bank’s leverage.

– What is the moral issue that banks need to justify? There is nothing immoral with borrowing, lending/investing, or borrowing to lend/invest. Legally, deposit contracts stipulate that deposits are loans and not being stored by the banks (I believe). Banks also borrow explicitly in debt markets (and once via issuing their own currencies/notes).

– I’m sure banking would look differently in a free banking regime. How specifically, I could only guess. However, I suspect that their “borrow to lend” model would not fundamentally change. In fact, many financial service companies are carry trades of some sort: banks, finance companies, insurance companies, hedge funds, and even mutual funds, though all to different degrees.

– Interest on borrowed money is paid for via new production, either from the passage of time or new capabilities. I illustrate the money making process in my latest article with an example. Perhaps that will help?

Yes, the “thin air” trope for creation of money is iffy. I prefer “high hopes and good intentions”. Although Paul Simon is also sometimes right: “pockets full of mumbles.”

Bank liabilities, that is, money in the form of deposits, are promised to pay state money on demand, backed by the bank’s assets which consist of mortgages, business and consumer loans, and the bank’s reserves and capital.