Image by Dinh Khoi Nguyen from Pixabay

Inflation is one of the most important, debated, and controversial investment themes today. It’s impacting every asset class from fixed income to commodities to equities. Yet, inflation’s widely misunderstood. While well-known among layman and expert alike, inflation’s definition changed over time. However, not everyone has noticed. As inflation’s meaning evolved, so too has its practical investment value. It no longer has monetary applications.

Inflation’s impact on monetary policy is partially to blame for investors’ hyper-focus (though it might play a smaller role than believed). Yet, many now question whether today’s inflation is monetarily driven or not. Ultimately, these disputes stem from inflation’s different meanings. It’s no wonder inflation confounds so many.

Not your father’s inflation

Much like money—and, in fact, because of it—inflation’s no longer consistently defined. Its meaning has evolved over time. What once stood for forceful monetary debasement now describes voluntary price changes. While they sound similar, these definitions subtly differ and describe to two distinct phenomena. Conflating them leads to vastly different conclusions.

Inflation once stood for currency debasement. Economists in the late 18th century used inflation to indicate when currencies lost their exchange value. It described when more currency was required to purchase the same goods and services. To these early economists, “inflation [was] something that [happened] to the circulating media at a given price level.” Specifically, it occurred when the currency supply was arbitrarily increased. Milton Friedman popularized this view when he famously proclaimed that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.” He implies that “money” should tightly correspond with output and that inflation occurs when the former increases more than the latter.

While not explicitly stated (a flaw), this historical use differentiates currency—a medium of exchange—from economic output—a.k.a. money. Properly understood, money is an abstraction for economic value. It translates real-world goods and services into common and monetary terms. Thus, currencies are not money. Rather, we use currencies to trade this value (i.e. money). Inflation does not (nor can) alter the value of money in this context. Rather, it describes when a currency’s ability to represent money degrades. To restate this Friedman’s terms: inflation is always and everywhere a currency phenomenon.

However, that began to change in the late 19th century, culminating with John Maynard Keynes. In his General Theory, Keynes redefined inflation as price increases. He severed it from a monetary context and generalized inflation to simply a rise in price. “What originally described a monetary cause came to describe a price effect”, notes one researcher (emphasis is mine). From then on, inflation referred to prices not a condition of currency. Its meaning changed. Inflation no longer referred to currency debasement.

Subtle changes big differences

Keynes’s change might seem small. After all, doesn’t a “general change in price” (GCP) capture the essence of monetary debasement? Doesn’t a currency buy less in both cases? This common error sits at the root of the inflation debate. While similar-sounding, they are not the same.

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduction in the purchasing power of money.

Source: Wikipedia

Debasement differs from a GCP in two fundamental ways. First, debasements occur instantaneously and ubiquitously to all prices. GCPs do not. In a debasement, the currency is revalued lower on a specific date(s). As a result, all goods and services reprice in currency terms at that time. After the U.S. dollar was devalued by the Gold Reserve Act to $35 per troy ounce of gold from $20.67, everything costed more in dollar terms: eggs, cars, doctor visits, theater tickets, you name it; everything except for gold. Gold was the monetary standard back then. Goods and services, however, were traded with dollars. The Gold Reserve Act changed the relation of dollars (the currency) to gold ( the money), not goods and services to gold. Their values remained unaffected in terms of gold.

Contrast this to GCPs. GCPs rely on an aggregation of prices. However, each price results from a unique transaction. Some prices go up and some go down, but all do not move together, even if they appear to do so “in general.” Some prices can fall while many others rise. These price changes also occur over time. Thus, GCPs differ from the instantaneous and ubiquitous nature of monetary debasement.

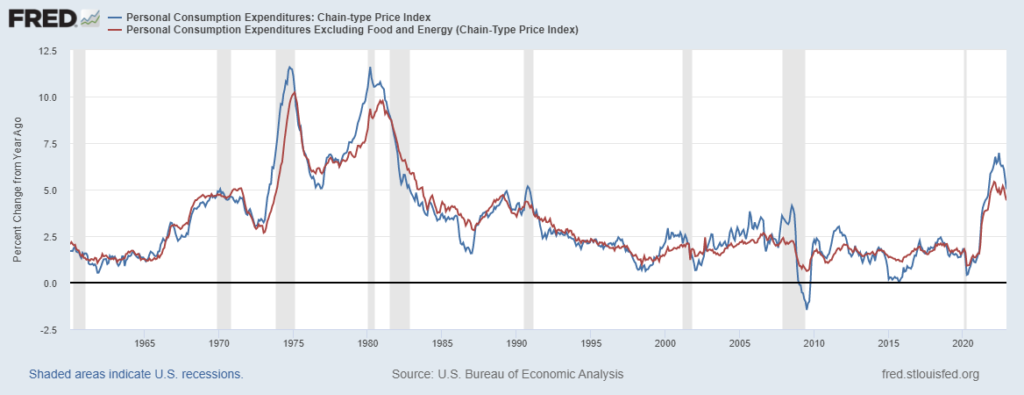

For example, market participants, including the Federal Reserve (Fed), typically differentiate core inflation from non-core. Both measure the price changes for a defined basket of goods and services. Both also represent measures of inflation today. Yet they are different price series. As shown below, core and noncore inflation do not always move in unison. They frequently decouple leading to inflation debates (when is there inflation and, if so, how much, etc.). GCPs can be ambiguous and subjective. Debasements are not. There are no divergent series.

Today there are many types of inflation like “core” and “non-core” which don’t always move in lockstep.

The second distinction between monetary debasement and GCPs is that debasements are political events where GCPs result from volitional transactions. Debasements can only be enacted by governments. Here, the sovereign decrees a change to the quantity and/or quality of currency representing money. Participants have no choice but to comply with the new currency standards (or face punishment). Thus, debasement is an act of force. Prices rise in response to currency devaluations. Debasement examples include the Gold Reserve Act’s impact on the U.S. dollar and the removal of silver from the Roman denarius towards the end of the republican period.

GCPs, though, do not (directly) result from government actions. In market economies, freely trading actors set prices (even if freedoms are restricted by laws and regulations). Thus, they change for lots of reasons relating to supply and/or demand, which are unrelated to currency matters. True, governments can impact prices for specific goods and services through spending and regulations. However, they occur over time and are ultimately limited in scope (i.e. they compete with other market participants). Furthermore, they may or may not have the secondary effects believed. It’s simply hard to tell. (Note, this is not a claim that government interventions are harmless.)

Shifted and confused

Today, any cause for rising prices is viewed as inflationary. Higher energy costs, wage increases, unfavorable weather conditions, union strikes, supply chain disruptions, foreign exchange movements, and an increase in circulating currency became equal inflationary pressures. While rising cost inputs might raise prices and reduce affordability, the lost purchasing power does not relate to the currency. They reflect a change in commercial conditions. Higher input costs lead to lower production quantities of goods and services and higher prices. In other words, inflation today represents shortages, not a currency devaluation.

However, because of central bankers’ Keynesian orientation—their demand-side perspective and modern inflation view—they now conflate inflation with economic growth! They seem to ignore the other components of GCP. It’s unclear if ignorance or the Fed’s myopic focus—to promote price stability and maximize employment via its Dual Mandate—is to blame. What is clear, though, is that: 1) monetary policy no longer relates to preserving the value of a U.S. dollar (there are no monetary standards to preserve in fiat currency regimes), and; 2) the macroeconomic impacts of adjusting the federal funds rate seem like rationalizations (see here for an elaboration).

Heading back to the future

Not everyone willingly accepts inflation’s new meaning. Many still cling to its monetary debasement context despite the shift to GCPs. Even the great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises erred. While he acknowledged that inflation no longer related to a faster rise in circulating currency than money, von Mises nonetheless asserted that “the general tendency toward a rise or a fall in commodity prices and wage rates” were “its [an increase in the currency supply’s] inexorable consequence.” Yet, we know that prices change for lots of reasons.

However, the fog is beginning to lift as today’s shortages are too obvious to ignore. In fact, even Fed researchers are questioning their views. For example, Adam Shapiro at the San Francisco Fed has attempted to disaggregate supply-driven inflation from demand-driven inflation, acknowledging that the former is unrelated to monetary policy. In many ways, this step backwards represents an economic leap forward. It brings us closer to seeing how changing inflation’s definition changed its role in monetary policy and investing.

An inflationary awakening?

Inflation is a foundational financial concept. Yet, it’s inconsistently defined by market participants. This results from a change in its use. What once meant monetary debasement to 18th century economists evolved into a GCP by the mid-1900s. Many underappreciate the subtlety of this change and believe them to be interchangeable.

Yet, monetary debasement and GCP differ in two ways. The former occurs instantaneously and affects all prices. Debasements also result from political edicts. GCPs, on the other hand, are market-driven. While government actions (like spending) can play a role, they only impact certain prices. Secondary affects are difficult to identify.

Any rise in price is considered inflationary today. Often, these result from changing commercial circumstances such as higher input costs, political events, or adverse weather conditions. Thus, inflation reflects shortages not a condition of a currency. It’s no longer a monetary issue.

Despite inflation’s clear definitional change, many hold on to its former meaning. They insist that GCPs are indicative of monetary debasements. Thankfully though, today’s environment led some to question this view. While market participants are far from rejecting inflation as a monetary issue, the inconsistencies have become too stark to ignore. Hopefully more will continue to see how inflation’s evolving definition removed its monetary applications.

If you enjoyed this article please consider sharing it with others.

So, I wonder, are you implying that monetary policy is no longer viable as a method to control inflation? While I agree that government actions, notably excessive (deficit) fiscal spending will certainly help push prices overall higher, is the implication that we need to see fiscal austerity if we are to control GCPs? If that is the case, there is exactly zero probability of a positive outcome in my estimation.

Perhaps a debt jubilee and the creation of a new currency, (perhaps we can call them Powells, or maybe Yellen’s in honor of those who worked so hard to debase dollars) is in order

I’m not implying, I’m stating that if we define inflation as a GCP then monetary policy has little impact on it. There are simply other factors at play that seem to be more important. That is not to say that monetary policy has no impact, just very little, in my opinion.

As I’ve written before, I think GCPs indicate shortages. Thus, their solutions are economic liberalization (i.e. deregulation and freedom). Austerity may or may not follow (but most likely would given our current context). I’d prefer to try this route to stimulate economic growth and grow into our debt load before resorting to debt jubilee and risk rinse-and-repeating our mistakes.

Thanks again for your comment.