Image by Stable Cascade

To this day, banking confuses many. The industry’s myriad of jargon and regulations can understandably perplex casual investors; however, they also confound experts—even those specializing in the discipline. Yet, banking is really quite simple. Banks borrow to lend. Their complexity is purely self-inflicted, created by the controls we’ve buried them under. Each new regulation adds to the burden bringing the industry one step closer to failure. The reflexive turn to regulatory solutions for industry hiccups reminds me of the old nursery rhyme: I don’t know why she swallowed a fly—perhaps she’ll die!

In 1952, Rose Bonne and Alan Mills copyrighted a song version of the children’s rhyme I Know an Old Lady. The familiar tune tells the silly story of an old woman who keeps swallowing animals. Beginning with a fly, the creatures successively grow larger. The woman hopes that her latest meal will catch the animal she previously ate. The behavior continues until the woman swallows a horse which kills her (of course!). As the story goes:

There was an old lady who swallowed a fly,

I don’t know why she swallowed a fly – perhaps she’ll die!There was an old lady who swallowed a spider

That wriggled and jiggled and tickled inside her;

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly;

I don’t know why she swallowed a fly – perhaps she’ll die!…

There was an old lady who swallowed a cow;

I don’t know how she swallowed a cow!

She swallowed the cow to catch the goat,

She swallowed the goat to catch the dog,

She swallowed the dog to catch the cat,

She swallowed the cat to catch the bird,

She swallowed the bird to catch the spider

That wriggled and jiggled and tickled inside her,

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly;

I don’t know why she swallowed a fly – perhaps she’ll die!There was an old lady who swallowed a horse…

Source

She’s dead, of course!

The banking business and its complex regulations resemble this old lady. What began as a relatively simple enterprise evolved into the Byzantine industry we know today. To a large extent, it resulted from the first decision to regulate banks as each successive rule tried to patch the unintended consequences created by the last. Swallowing that fly is slowly leading to a horse.

Still dazed and confused

It amazes me how poorly we understand banking today. Banks are everywhere. They once populated nearly every corner of America before digitizing. According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), more than 80% of U.S. households were “fully banked” in 2021. Yet, despite our familiarity, centuries of operating history, volumes of books, countless academic papers, and dozens of overseeing regulatory agencies, banking still confuses and scares many.

A recent podcast reminded me of this. When the expert guest answered the question of “what does a bank do,” with “deposits,” disagreement and discussion broke out. The hosts concluded the interview with the discussion point that “… big picture, I feel like in the U.S. we have yet to decide what we want the banking system to actually look like … .” With perspectives like these, banking problems should not surprise us. They cause them!

Lenders not storers

First, “deposits” is not the primary business of banks. If it were, they’d charge fees for it. Instead, banks pay depositors to access their funds and often provide ancillary services like checking and ATM access for free. They assume these costs to acquire capital needed to support their primary business purpose just like a steelmaker pays suppliers for the iron ore it needs to transform.

Banks are in the lending (and investing) business, not the money storage business (i.e deposits). They are carry trades, borrowing money in order to lend. Hence, all deposits are legally classified as liabilities and depositors are considered creditors. If banks truly stored funds, rather than borrowed them, they’d hold deposits as legally separated accounts like investment managers and other custodians.

In fact, banks didn’t always accept deposits. They primarily issued banknotes to support their lending activities until (virtually) outlawed. Only then did deposit-taking grow in importance. Today, banks also fund their operations in the capital markets, issuing commercial paper and corporate bonds and transacting in repo markets, for example. These channels provide banks with low-cost capital that they can subsequently lend at higher rates. They profit from this rate differential known as their net interest margin.

There’s no “we” in banks

Furthermore, banking is not a service, communal activity, or tool for public good. It’s a business. Banks exist to generate a profit for their owners. Like all profitable businesses, they improve society as a consequence.

Thus, “we” have nothing to say with respect to how the banking industry should look. That is for the bank owners to decide. In a free society dominated by voluntary trade, competition among banks shapes the composition of the industry from the products and services they offer to how they legally organize. What services they should provide, to whom, and for how much; how much capital they should hold and in what forms; what types of loans they should make, to whom, and at what rates get shaped by the trillions of interactions between various banks, capital providers, and customers over time.

Yet, banks lack such freedom today. Instead, myriads of regulations guide their every action. Federal agencies like the Federal Reserve (Fed), FDIC, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency oversee some. Individual states have their own slate of compliance departments and there are even supranational standard-setters like the Bank for International Settlements. Each one subjects banks to its own guidelines. While often benevolently motivated, their rules can conflict, confusing management teams and exposing banks to legal liabilities and selective enforcement risks. Often, these regulations create the behaviors we despise and fear.

Legacy of restrictions not laissez faire

While the Fed’s founding in 1913 represented an escalation of bank supervision, American banks were tightly controlled since inception. The country’s founders debated how to permit the industry’s existence, eventually modeling it on England’s with which they were familiar. At the time, England’s banking sector had recently centralized around the Bank of England following the passages of the Bubble Act and Tunnage Act. As a result, American banks required state and federal approvals to operate. As Bray Hammond noted in his Pulitzer prize-winning book on early American banks:

The early years of the republic are often spoken of as if the era were one of laissez faire in which governmental authority refrained from interference in business and benevolently left it a free field. Nothing of the sort was true of banking. Legislators hesitated about the kind of conditions under which banking should be permitted but never about the propriety and need of imposing conditions. … The issue was between prohibition and state control, with no thought of free enterprise. … To be sure, all these laws were charters of incorporation, and an incorporated bank had no rights other than those given it by its legislative creator.

Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War (pg. 185-186)

Restrictions limited the number of locations banks could have, where they could operate, the types of products and services they could offer, and other aspects. For example, between 1802 and 1826 nearly every bank charter in Massachusetts “required that a certain number of loans be agricultural, be secured by mortgage, and run for at least a year.” Certain Maryland charter renewals required banks to invest in a company formed to construct a turnpike; Pennsylvania mandated “the forty-one banks to lend one-fifth of their capital ‘for one year, to the farmers, mechanics, and manufacturers’ of their districts.” Politics, not enterprise, shaped banks.

Even the “free banking” period in the U.S.—from the 1830s to the Fed’s founding in 1913—was a misnomer. “Free” referred only to the relaxation of requirements to open a bank, not an environment free from regulation. All remained subject to state banking laws. In America, banks never operated with the same autonomy afforded to other industries.

It is important to keep in mind that free banking is not the same as laissez-faire banking, in which there is no government interference of any kind. Free banking simply means that no charter or permission is needed from a government body to start a bank, unlike the current chartered banking system in the U.S. The free-banking laws specified that a state banking authority determined the general operating rules and minimum capital requirement, but no official approval was required to start a bank.

Daniel Sanches. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Research Department, The Free-Banking Era: A Lesson for Today?

The banking industry has always been heavily controlled in America. According to Hammond, the initial restraints only increased through the Civil War. This legacy continues.

Controls beget control

The trend of increasing controls continues to the current day. Each financial crisis begets a new slate of regulations with which banks must comply devised to cure deficiencies of the preceding regime. However, the existing regulations often caused that which the new ones seek to rectify.

For example, I previously noted how banking regulations created the interest rate vulnerability that led to the failures of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, Silvergate Bank, and First Republic Bank last year. By incentivizing (and requiring) banks to hold “high-quality” and “liquid” assets, they consequentially owned large quantities of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities issued by U.S. government agencies (such as Fannie Mae). While virtually riskless from a credit-loss perspective, these securities carried large interest rate risks which blew holes in the banks’ balance sheets as the Fed aggressively raised its policy rate. Regulations—in part—motivated the behaviors that caused the banks to fail.

Those regulations were, of course, instituted in response to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-2008. Intended to prevent the types of capital losses experienced then, they instead created unintended vulnerabilities felt in 2023. The GFC resulted from regulations governing banks’ capital requirements that centralized risks by codifying the credit assessments of a handful of sanctioned rating agencies into banks’ investment decisions and laws requiring banks to extend questionable, housing-related loans. Those laws, unsurprisingly, were enacted to “encourage” banks to extend credit to households that they might not have otherwise.

The Fed was also created to rectify perceived banking system shortcomings. A slate of financial panics plagued the decades preceding its establishment convincing some that a central bank was needed to bring stability to the volatile sector. Yet, those “market failures” also resulted from various laws common to the time, such as the prohibition of branching and the requirement to collateralize banknotes with government securities. The former prevented banks from diversifying their credit risks, funding sources, and liquidity measures. The latter curtailed lending activity as the U.S. government repaid its debt leaving banks short on capital to lend. That requirement, of course, came from the National Currency and National Bank acts which were passed to help finance the Civil War.

Since the very beginning, we’ve sought regulatory solutions for regulation-created problems with banks.

More regulations lead to bigger problems

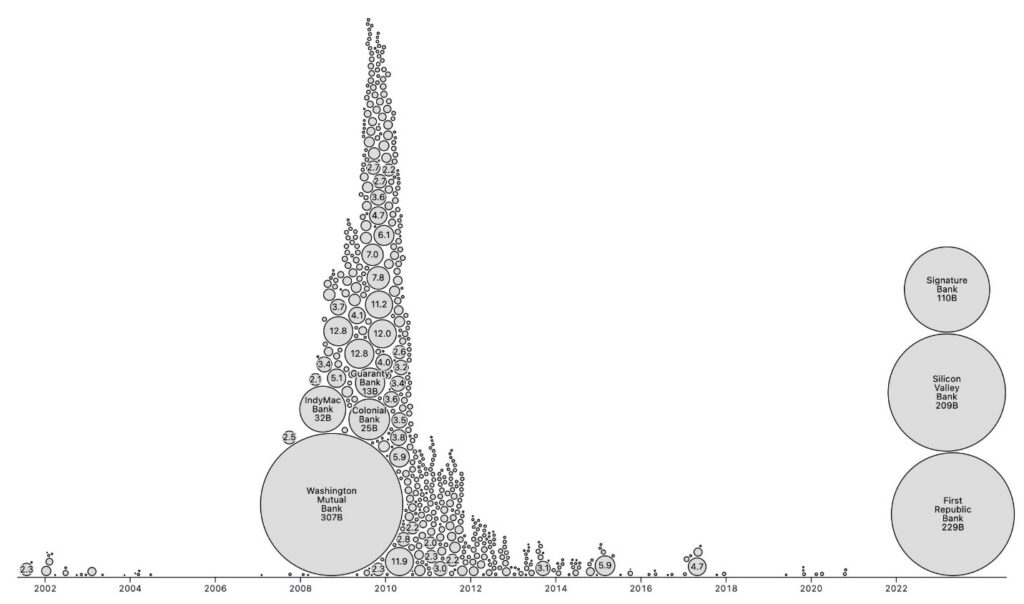

However, regulations centralize risks thereby increasing systemic fragility in the banking sector. They drive consolidation and incentivize the larger banks to behave in similar ways. Rather than alleviate crises, regulations sow the seeds of the next, larger one. Note that the collapse of just 5 banks made 2023 the second largest year for them in U.S. history. Many more had to fail in previous episodes to register.

The collapse of just 5 banks (3 shown in the graphic above) made 2023 the second largest year for bank failures in U.S. history. Source: https://observablehq.com/@mbostock/bank-failures

Financial system stability requires decentralization. That entails fewer and looser, not more and tighter controls. Thus, regulations should be lessened to facilitate risk diversification by permitting a greater number of actors and actions. While potentially bumpy, there’s no other way to reduce the risks inherent in banking. More controls can only create greater instability and lead to the sector’s eventual demise.

Don’t swallow a horse

The banking industry unnecessarily confuses and scares many. Its complexity stems purely from the growing regulations that saddle it. Absent those, freely transacting customers and capital markets would determine banks’ products and services, risk management practices, and organizational structures optimizing for profit, customer satisfaction, and value-creation.

Unfortunately, we have yet to learn the centralizing dangers that result from bank regulations. By incentivizing banks to consolidate and act similarly, they create unintended systemic risks that manifest as future panics.

Contrary to popular narratives, banks have been tightly controlled since America’s founding. Economic and political freedom had just been discovered so modeling the industry on England’s seemed logical. As a result, politics, as much as profits, shape their operations. Yet we blame their failures on enterprise, not the regulations that motivate their behaviors. By seeking regulatory solutions to regulatory-created problems, we virtually guarantee the next crisis.

Like the old lady, we’ve tried swallowing spiders, birds, cats, dogs, goats, and cows to cure our banking ills. Let’s hope we learn our lesson before we get to the horse.

If you enjoyed this article please consider sharing it with others.

Enjoyed this sharp perspective!

Thanks for the comment!

Alas, we will never learn the proper lessons. history has shown time and again that every politician and regulator believes ‘more is more’ and will always seek to layer on new rules that can benefit them either personally or politically.

While I would love to see the FDIC eliminated and people forced to pay attention to their bank’s financial situation, I know that the education system in this country has deteriorated so far that almost nobody would have any understanding of what to even consider.

but ultimately, the biggest problem, in my mind at least, is that restructuring banking (or any) regulation would be akin to less government. and until everything implodes there is absolutely zero appetite for that process to occur politically going forward, regardless of the party in charge.

Thanks for you comments and readership Andy.

Yes, restructuring is the only answer. However, I firmly believe that it can be done without a catastrophe nor that a catastrophe would bring about change. Regulatory change can only come from a change in economic/political/philosophical ideas. The American Revolution, for example, is an example of a major radical change that did not follow catastrophe. Thus, to truly improve our economic resiliency – banking industry included – we need to advocate for better ideas (i.e. decentralized control, a.k.a. economic freedom).

If you “borrowed to lend,” you might borrow money at 3% to lend it at 6%. If you did that, your balance sheet would not expand when you loaned your clients’ money, because you would simply swap one asset (your clients’s cash) for another (the borrowers’ IOU). If you did all this, you would not be a bank, but a financial intermediary, like a hedge fund, or a money market fund, or a bond fund, etc.

This is not what commercial banks do. When a bank lends, it acquires a loan (or a bond) as a new asset. The bank pays for this investment by creating a new liability called a bank deposit. This new deposit is an addition to the money supply. A bank deposit is a promise to pay out cash reserves, and it circulates as money by moving from one bank account to another. Tellingly, the entire balance sheet of a bank enlarges when it makes a loan, and contracts when the loan is paid off.

The ability to “create money” in this way is the unique feature that makes a bank a bank.

If, as you say, banks, “borrow to lend,” how can we account for the increase in the money supply – money supply being the total of bank deposits and currency in circulation? Where do all the new bank deposits come from? Can you describe the mechanism of their creation?

On one point I will agree: banking regulations are ridiculous.

Thanks for your readership and comments Jim.

When a bank borrows $100mn (via deposits, bonds, repo, etc., it doesn’t matter) and extends a $100mn loan, its balance sheet expands by $100mn. Both sides literally increase by $100mn (equally). If a bank’s successful at lending the $100mn at 6% and borrowing at 3%, to use your example, its balance sheet will grow by an additional $3mn to $103mn – accounting for the $3mn of net interest margin profit (assuming no admin/ops cost). Thus, successful lending permanently creates new money (the $3mn) and unsuccessful lending eventually destroys it (the $100mn less recoveries). This asymmetry comes from the process of using leverage (i.e. borrowing to lend).

If you narrowly define money as “the total of bank deposits and currency in circulation” then – by definition – only banks can create money. If you define books as “books in libraries” then you’d find that only libraries have books and miss the countless other books residing in private libraries, homes, bookstores, and in digital form. You’d also misunderstand how book creation works due to the hierarchy error.

Money is more than bank accounts. It’s an abstraction for and the quantification of things that exist in the world. Bank accounts are just a portion of the picture like library books (above) are just some of the books.

Here are some links were I discuss these views more, each with links to others:

https://integratinginvestor.com/banks-create-money-from-leverage-not-thin-air/

https://integratinginvestor.com/logically-defining-money-makes-cents/